Digital generative art is when an artist trusts an algorithm to make some decisions for them.

It's similar to etching: multiple prints can be made from a single plate. An algorithm can similarly create many copies: the resulting works differ from each other but preserve a common structure. The main challenge for the artist is finding the balance between chaos and structure, choosing an algorithm that creates compositions that are diverse yet always good.

A separate class of generative systems is emergent ones. In them, simple rules of particle interaction lead to complex behavior and pattern formation that are hard to predict in advance. Examples of such systems include simulations of physical and biological processes.

Levels of modeling

The model has several levels:

- Physical

- Biological

- Cognitive

At the physical level there are single-celled organisms, each with its own speed and position. Space is divided into tiny pixel cells, each storing data about only one organism.

[Video of cells up close here]

At the biological level energy appears in the model. Organisms spend it on movement; during reproduction, energy is divided between offspring. Without energy, organisms die.

They can get energy either from the environment or by eating neighbors: when several organisms end up in one cell of space, only one survives — the one with more energy. It eats the others and replenishes its energy supply.

At the cognitive level — organisms have a genome that determines their behavior and color.

The genome consists of 64 numbers from 1 to 64. Values can be perceived by the organism as commands, for example:

- accelerate,

- decelerate,

- turn,

- check energy balance,

- get energy from surrounding space,

- reproduce

There's also a conditional jump command to another part of the DNA when certain conditions are met. This makes organism behavior dependent on conditions: the organism's energy level and the nutrient gradient in the environment.

Genome values can serve not only as commands but also as command parameters. For example, what angle to turn or what probability to mutate during reproduction.

Initially, DNA is assembled from random EEG fragments. Most organisms die immediately: some don't feed, others spend energy on movement or reproduction faster than they accumulate it.

Among the many organisms with random DNA combinations, only a few survive, giving rise to "islands" of their populations.

Each organism's genome is passed to offspring with small changes, thus the population increases internal diversity and adapts to changing conditions.

Implementation

The script is written in JavaScript with WebGL. Organism parameters and their DNA are stored in eight float textures. EEG data is decomposed by frequency using Fast Fourier Transform, aggregated, and passed to the shader. Computation happens in the browser in real time.

More details to come about:

- Particles on fragment shader

- "DNA" program structure

- Data storage

- Program interpretation

- Commands and parameters

- Conditions

- Reproduction

- Mutations

Particles on fragment shader

I took the algorithm idea from Mikhailo Moroz's blog: four pixel channels (RGBA) can be used to store particle coordinates and velocity on a plane. It's interesting to compare this method with the more popular particle control method — the vertex shader.

| Particles on vertex shader | On fragment | |

|---|---|---|

| Idea | Particle calculates its coordinates | Pixel calculates position and velocity of its particle, if there is one |

| Data storage | In FBO or buffer | Particle in pixel that stores info about it |

| Max speed | Any | 𝓋=1…~3px. Each pixel checks if a particle flew into it from 𝛑𝓋² neighbors |

| Particle count | Fixed. Lag starts after 1M, depends on behavior complexity | Can change. Particle count limited by texture pixels, count doesn't affect speed. Only number of checked neighbors affects speed |

| Interaction | Particle doesn't know if others are nearby | Particle can look at neighboring pixels and interact with their contents |

| Collision | Don't collide | If two particles fly into one pixel, one overwrites the other |

| Debug complexity | ᕕ( ᐛ )ᕗ | (ノಠ益ಠ)ノ彡┻━┻ |

For simulating cellular life, the fragment shader is more convenient: they can multiply indefinitely, attract or repel.

Data storage

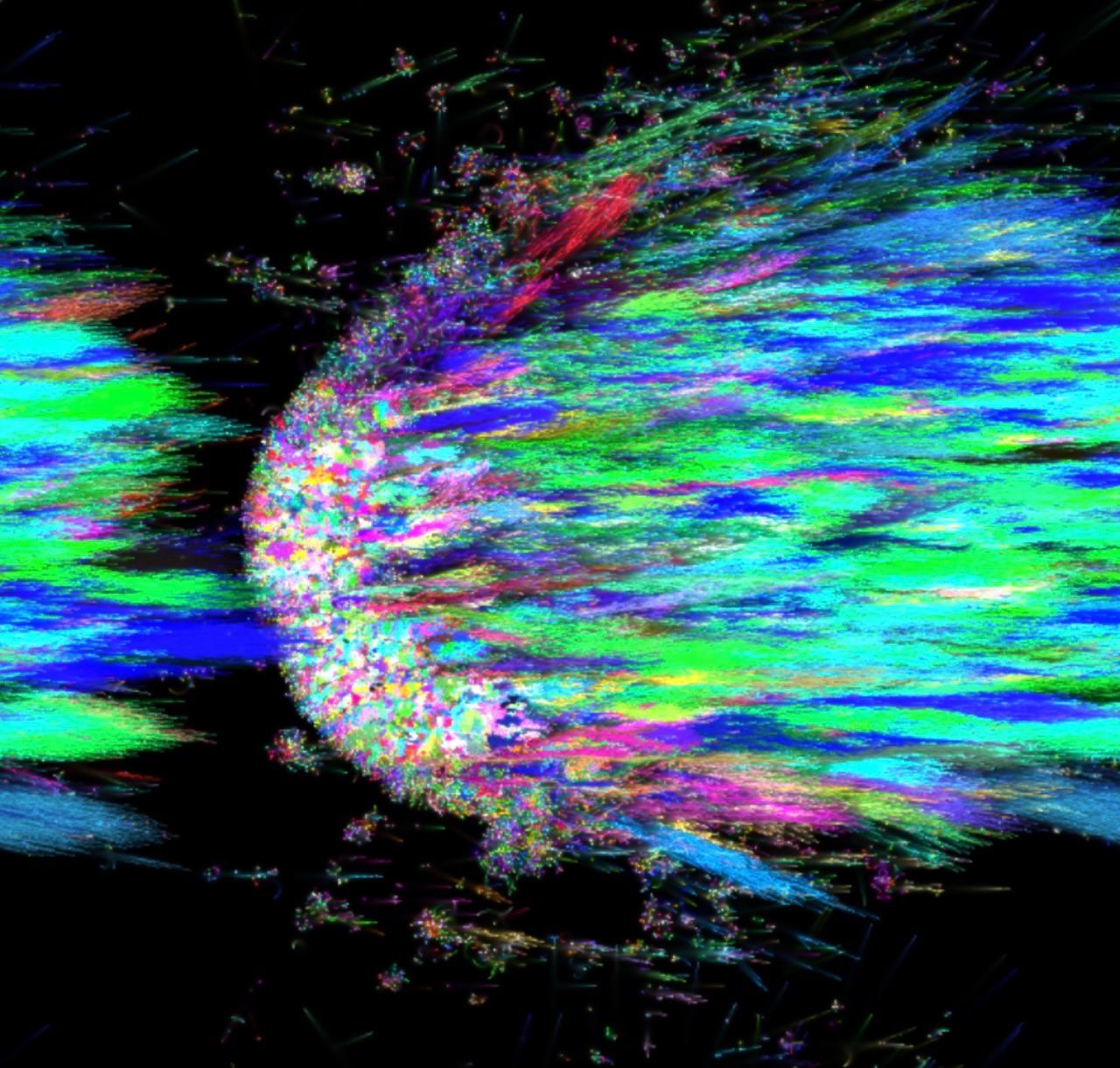

Picture shows many tiny cells, each secreting colored substances. Which ones depends on DNA, as does cell behavior: turns, speed changes. Genes are passed to offspring during division

Picture shows many tiny cells, each secreting colored substances. Which ones depends on DNA, as does cell behavior: turns, speed changes. Genes are passed to offspring during division

I liked TechnoShaman's idea about DNA interpretation. In short: each cell has "DNA" — an array of 64 elements, each can take one of 64 values. The cell also remembers the number of its current command. Commands can be simple: "move", "reproduce", or tricky: "if energy is above 10 units, go to command 5, otherwise — to command 43".

My implementation has two main differences: code runs on shader (can compute more cells faster) and there's physics: cells don't live on a grid but on a continuous plane, can smoothly accelerate and decelerate. I also want to add pheromone response.