How It All Began

When I was a kid, I dreamed of being an inventor.

There was no computer at home, so I used grid paper instead. On it, I simulated cellular automata, invented my own step-by-step games, drew schematics for sleds with electric drives, and kites. I also loved building things from old construction kits that my dad gave me. Our family wasn’t wealthy, so the kits were secondhand and often missing parts. Sometimes, to build a microscope or binoculars, just one small part would be missing.

My cousins had a computer, and when I went to visit them, I would watch them play games. But when my turn finally came, instead of playing games, I preferred to code simple HTML pages.

When my grandfather bought me a computer, I immediately installed several games. But instead of just playing, I loved hacking them. Honestly, just playing games felt stressful and a bit scary. By programming games I was stepping out of the game's samsara with its missions, enemies, and goals. I moved up to another level — I became the master of this virtual world! I could invent my own missions, create a million enemies to run around chaotically or march in parade-like lines. Writing my own rules was far more thrilling than playing by someone else’s.

Things got even more interesting when a few nerd friends and I signed up for the school's computer club, which was affiliated with the university. There, we used Borland C++ to create simple games with pixel art and basic animation.

I had become an inventor — my dream had come true. Programming became a magic construction kit where I could create any missing part myself.

Background

This engineering creativity captivated me to the point that I entered a technical university and completed a master’s degree in Computer-aided design.

I don't have formal education in art or design, but I did attend art school and experimented with various visual techniques: linocut, cyanotype, film photography, and, of course, stencils for street art! In all of these processes, the most mesmerizing part was the moment of unveiling — when you lift the stencil or develop the film. A moment ago, nothing was there, and suddenly, an image appears. The result depends not only on my skills but also on the stencil itself, on how the spray paint lands. It's impossible to predict the outcome entirely; it's a collaboration with the world, with the complex, unpredictable nature of physical reality.

Maybe that’s why I gravitated towards data visualization — it seemed like a logical extension of this idea of making the invisible visible. I was also searching for a way to combine visual art with my programming skills, and data visualization fit perfectly!

Sometimes, my data visualization scripts had bugs, and the resulting glitches delighted me. I’d post them on social media and often felt prouder of them than of the final, polished results. I even began experimenting with data art, which some joke is “data visualization without a legend.” It took me a couple of years to admit that data visualization is often way more exciting when you take out the data. That’s when I discovered code that visualizes only itself.

In data visualization, there’s a concept called “indexical visualization” — where a phenomenon visualizes itself. For example, smoke in the air shows its own movement. Generative art is a similar concept: code visualizes its algorithm, and the resulting artifacts reveal its nature.

Some of my favorite generative systems to experiment with include cellular automata, L‑systems, particle simulations, slime mold, and fractals. They all follow simple rules, but create complex and interesting visualisations that allow you to explore the mathematical reality in which they exist.

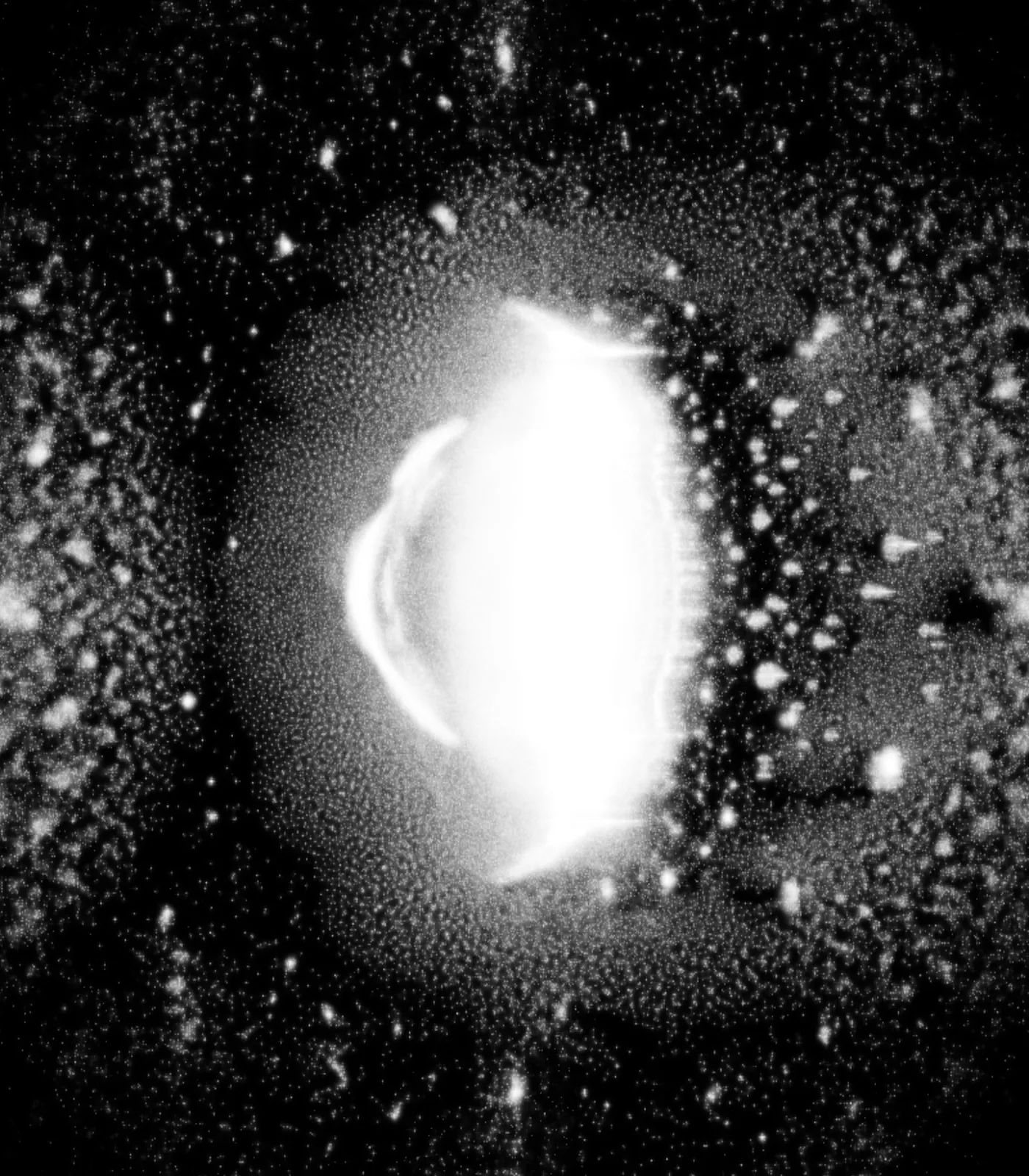

A modification of a physarum simulation algorithm

A modification of a physarum simulation algorithm

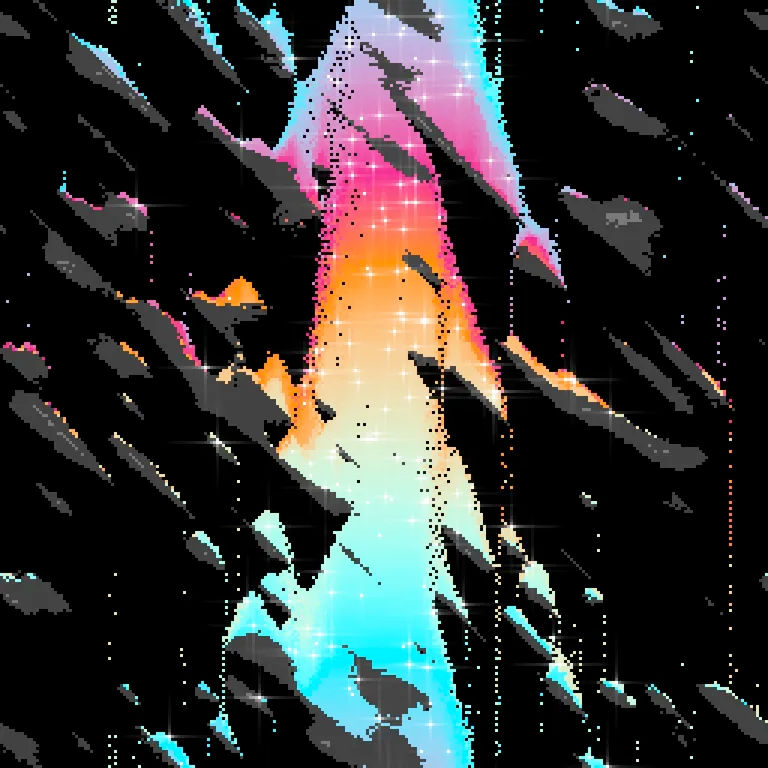

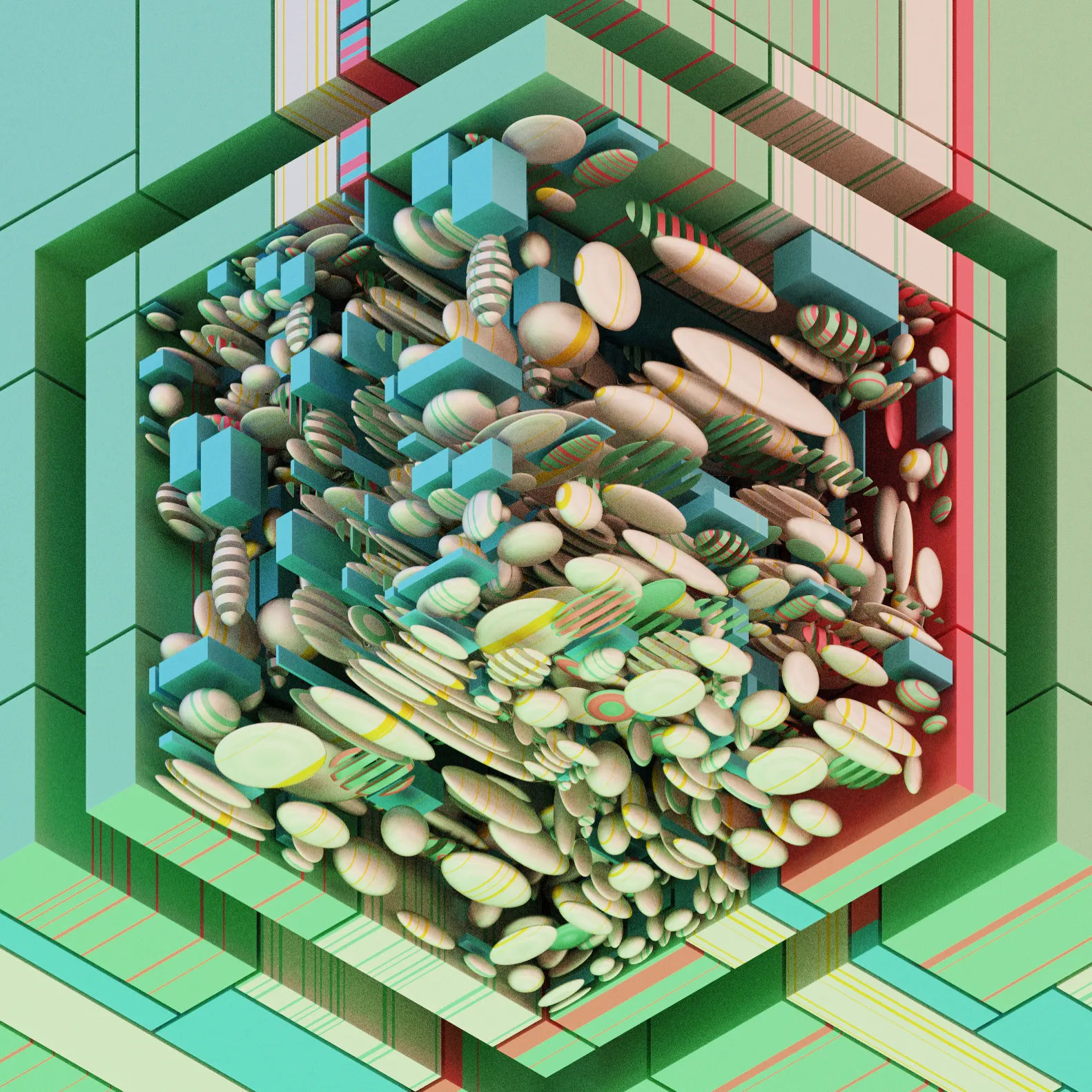

A fractal corridor made during a livecoding session

A fractal corridor made during a livecoding session

A deterministic sand simulation with cellular automata

A deterministic sand simulation with cellular automata

Live Coding and Unpredictability

Both in life and programming, unpredictability matters to me. If everything’s predetermined, I lose interest. That's why I enjoy livecoding so much, when I program procedural graphics on stage in real time and improvise. Even if I rehearse before a performance, every rehearsal and the performance itself is a surprise to me. I can suddenly get some effect that amazes me.

Even when the code is small, my brain can’t grasp all its complexity, so I can’t fully understand how a given fractal forms. This adds an element of unexpectedness and unpredictability. Sometimes, I feel a sudden urge to delete or randomly modify code fragments, and sometimes a single character change transforms the screen completely. It’s thrilling and hypnotic, keeping me glued to the screen.

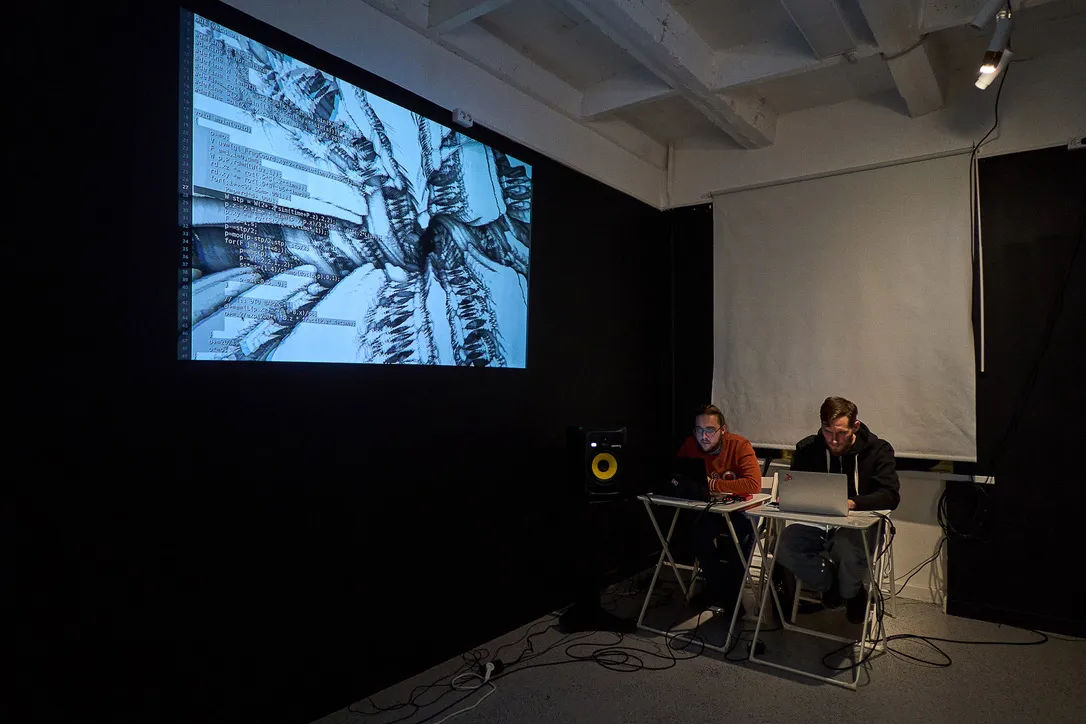

Livecoding performance at the museum

Livecoding performance at the museum

In livecoding, the concept of “Truth to Materials” is also important to me.

Truth to Materials

Truth to Materials — an architectural concept emphasizing the importance of not concealing the natural properties of materials. For example, concrete should not be painted or polished to hide the traces of formwork.

I like applying this concept to generative art techniques: letting the algorithm determine the final look.

Instead of embellishment, I aim to write minimal code that can create an image. Something simple, black-and-white, without smoothing or frills. It doesn’t pretend to be a render from Cinema 4D; it calculates instantly and looks bold and raw.

Digital art has its own aesthetic that doesn’t need to be styled to mimic other techniques like painting or watercolor drips.

If the image is a raster image, let the pixels be noticeable. If it's a raymarched image, let the signature glitches be eye-catching. Why shy away from roughness? You can use it as a unique texture, as an idea, and give them the most prominent place in your work.

The Influence of Lo-Fi Culture

I used to love taking pictures with a Dirkon, a pinhole paper camera. Before that, I used to take photos on a matchbox with taped reels and a paper clip to advance the film. This downshifted, lo-fi approach was inspiring, I liked that you didn’t need an expensive camera — just a matchbox, and then you could develop the film with some strong coffee.

I enjoy achieving results with primitive tools. In programming, I like it when the code is as short as possible. In practice, it's rarely needed, except when sizecoding is valuable in itself. For example, there's a Twitter challenge #つぶぶやきGLSL when you need to fit a fancy shader into a tweet. When I was preparing the Click project for Art Blocks I also was enthusiastic about shrinking the code size. It's a magical feeling when the source code is condensed to a small rectangle that is entirely visible on the screen.

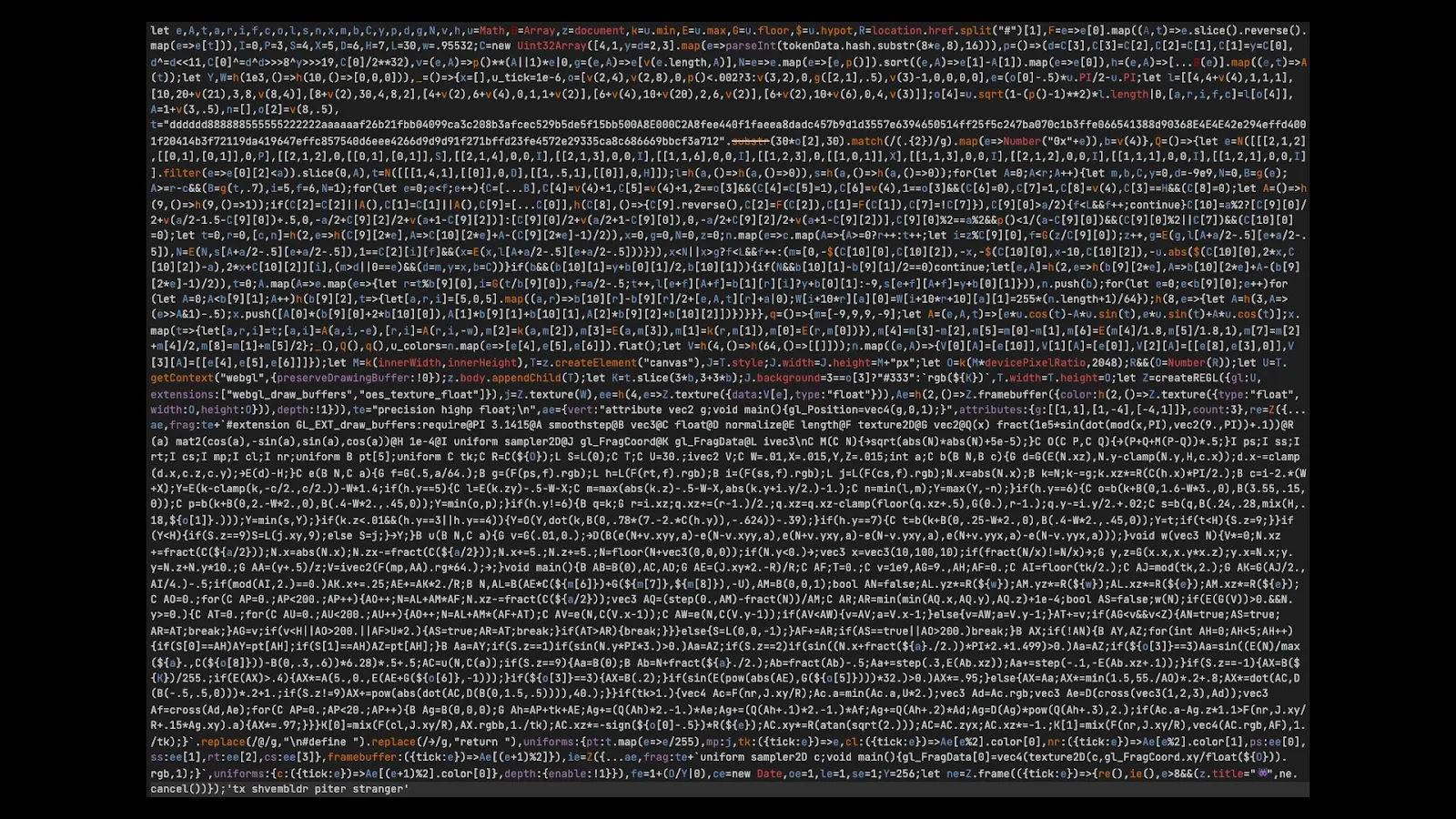

The source code of the Click project

The source code of the Click project

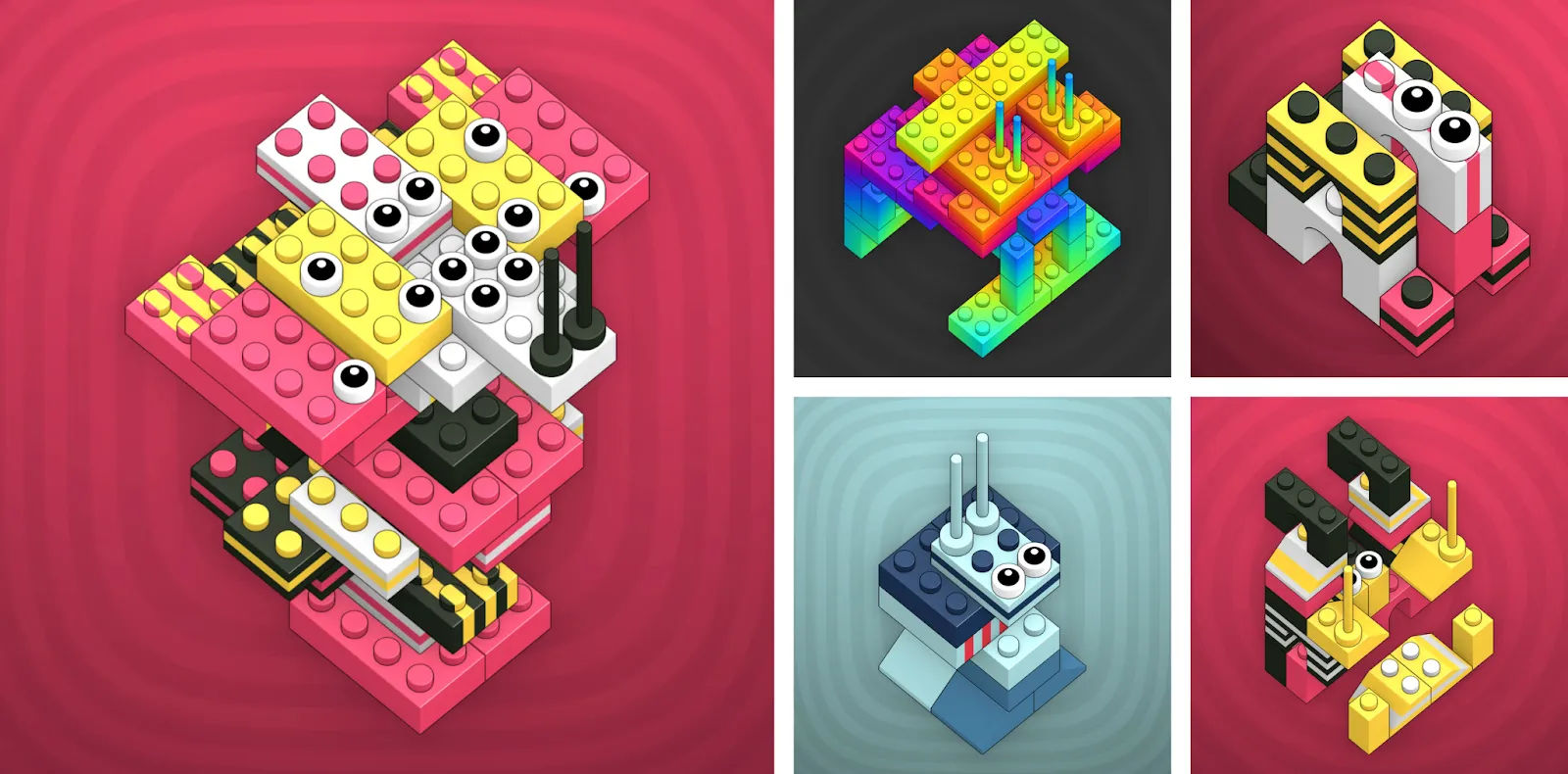

Several outputs generated with the code above

Several outputs generated with the code above

Some results of the above script

This practice of creating minimal code is handy for livecoding performances and shader battles as well. I can quickly write a tiny ray-tracing engine with just a few characters, saving time.

The limitation of the code size makes you creative and resourceful. For example, one and the same function can be used for both macro and micropattern, as in Wholeness Mirage.

Wholeness Mirage uses the same pattern for micro and marco levels

Wholeness Mirage uses the same pattern for micro and marco levels

Such limitations can affect the work making a photo, stencil, or generative art piece coarser. I used to struggle with this, striving for perfection, but over time, accepting the imperfections in myself and my work has become an important theme. It’s a practice and philosophy for me — not polishing a piece to perfection but finishing it as spontaneously as I started it.

This principle also applies to my tools: I use a simple text editor neovim and can't use IDEs. They are convenient, but very visually heavy. With my ADHD, reducing visual noise is a necessity.

ADHD

I’m not sure if I have ADHD, but sometimes I get distracted every minute, while at other times, I get so absorbed in my work that I’m impossible to pull away.

I once tried to discipline myself — blocking social media, setting daily goals, writing myself progress reports.

At some point, I realized that I didn’t need to defeat myself but rather adapt to my peculiarities. Around that time, I stopped setting rigid goals or making task lists. I began using my oddities instead of fighting them.

For example, I sometimes can't talk myself into a task for hours. It helps to set a timer or — supercheat! — to start a task and soon leave it unfinished, so that I can itch to finish it.

Even the hyperfocus characteristic of ADHD has been super helpful for focused work. But it took me a while to learn how to get into it. In the case of generative art, I need to get excited about an idea, to come up with an innovative combination of techniques that I want to show to the world. This was the case, for example, with curvoxel-hybrid raymarching and Zero-player game

Antigravity #35

Antigravity #35

Zero-player game #1 is an infinite plane filled with never repeating pattern

Zero-player game #1 is an infinite plane filled with never repeating pattern

Another way is to find an inspiring reference. Architecture and biological processes are an endless source of inspiration for me.

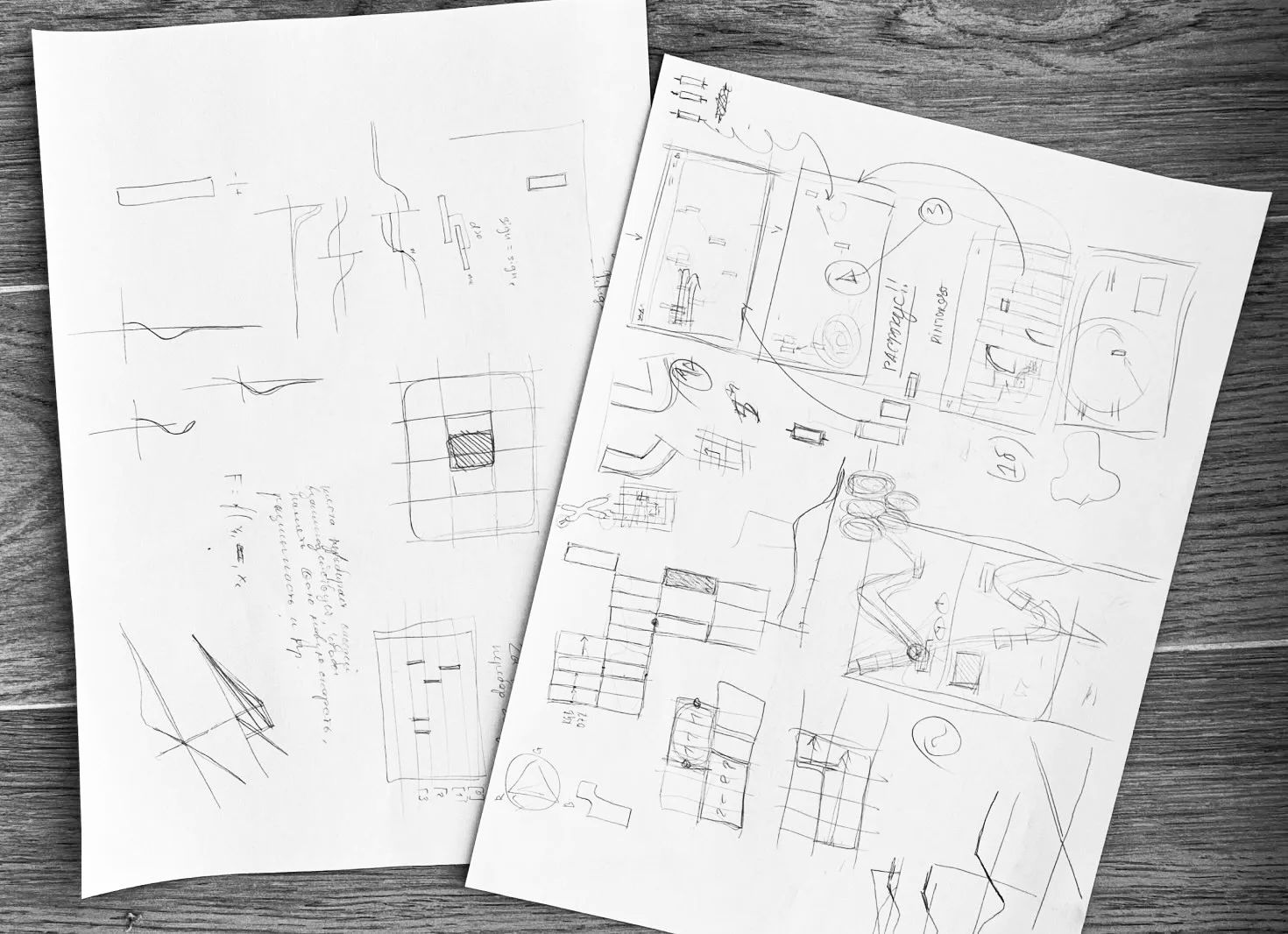

Often when programming I can't keep the whole picture in my head, I have to draw diagrams on a piece of paper or a chalkboard, for this purpose I painted some walls in my flat with black board paint.

First sketches for a commercial project

First sketches for a commercial project

Another way to stay focused is through the sense of flow, and a quick result is essential for that. I couldn’t get into working with neural networks — they take too long to yield results, let alone training one on a custom dataset. Shaders and javascript, on the other hand, show results instantly, and that's what hooks me.

Generative art has become a tool for self-discovery, a job, a way to relax, a bundle of threads connecting me to this world.

I work in three areas: art, commercial commissions (I collaborate with designers and agencies), and education. It’s important to me to share with students the vibe and excitement that programming brings me.

For those who haven’t tried it, I recommend giving it a go. You might just enjoy it! The key is not to strive for perfection and to appreciate small victories.